Thoughts on Culture…and Other Sordid Things

by Brent McCulley

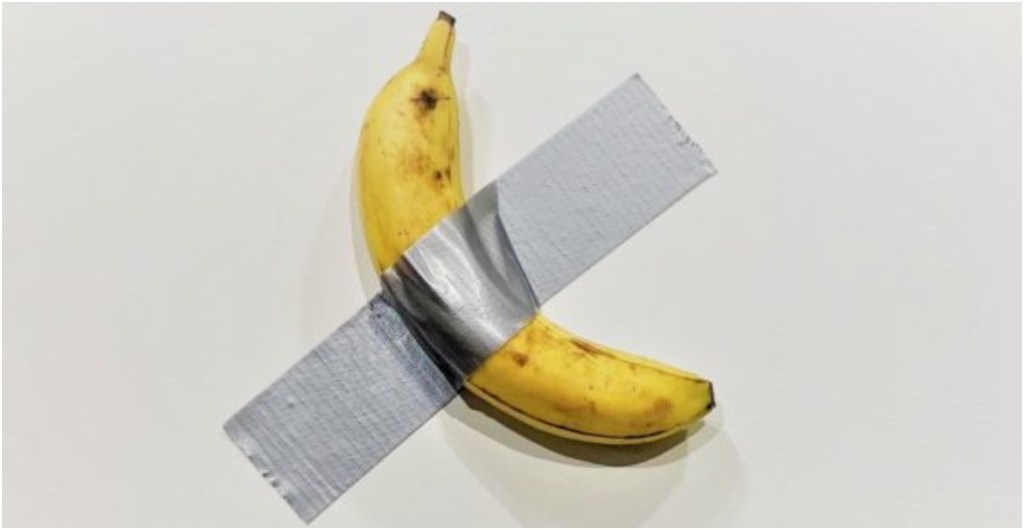

America today is a cultural vacuum. There is now much talk and recent concern about AI slop, yet this metaphor is not more apropos than the products of our current culture. A culture need not produce something that is sui generis in order for it to be considered the paragon of aesthetics. Indeed, one can think of Milton’s Paradise Lost or Goethe’s Faust as examples. For Lord Byron doesn’t write Don Juan without Tirso de Molina; neither does Beethoven compose the final movement of his Ninth Symphony without Schiller’s Ode to Joy. All are still considered classics, and for a just reason. Yet just because something is unique, or sui generis, does not mean that it is ingenious. Sui generis is a Latin term in the genitive case meaning literally of its own genus or species. Ingenious comes from the Latin ingenium meaning that which is inborn. Our current culture is not ingenious with inborn qualities but stillborn qualities, however unique our cultural products may appear. It generates—its productions are not full of life but death. This is not entirely without purpose, however. There is indeed a shock and awe factor to gape dumbfounded at this abortivus infans and surreptitiously look around to see if there is laudation or laughter before one makes a peep. Thus, as there is no air left in a vacuum, so too there is no l’esprit left in our cultural vacuum. There remain only residual gaseous particulates that defy explanation—this is the substratum of all our art, music, science, and philosophy.

Even as AI slop is permeating our horizon, there is no rhyme or reason for our human productions and thus we are scrambling for a philosophical Grund to make a contradistinction. This is because there is no longer a contrast, there are only ever-increasing levels of homogeneity. As Shakespeare penned in his Comedy of Errors:

Was there ever any man thus beaten out of season,

When in the why and the wherefore is neither rhyme nor reason?

We ourselves bear no “why” and “wherefore” at all, let alone a spirited rhyme or reason contained therein. And thus, it behooves oneself to take it upon themselves to “beat the man,” that is to say, our stillborn culture, out of season. Perhaps this sounds shocking, but this is not without precedent. Nietzsche himself exercised quite the lashing in the first essay of his Meditations Out of Season, a critique of late nineteenth-century German culture. This era prided itself on being the consummate culture and exemplar of the highest culture of art, music, science, and philosophy, and Nietzsche berated his fellowmen as being nothing more than barbarians and cultural philistines. Commenting on society’s penchant to banish old greats and quickly declare new “classics” Nietzsche retorts: “[Our] public opinion in aesthetic matters is so insipid. Uncertain and easily misled that it beholds such an exhibition of the sorriest philistinism without protest, that it lacks, indeed, any feeling for the comicality of a scene in which an unaesthetic magistrate sits in judgment on Beethoven” (David Strauss. The confessor and the writer, 5). In an early scene of the movie Tár (2022), the famous conductor and composer Lydia (Cate Blanchett) chides a student, while teaching a class at Julliard, for his feckless dismissal of the entire Western Cannon because men like Beethoven, Bach, and Mozart were white males. The scene, surfeited with tension, perfectly encapsulated the clash between the old order and the new. The old canon is now insufferable and must be deposed, thereby declaring new instant classics—the sloppy stillborn productions of our sterile society.

Nietzsche’s essay was ostensibly a critique of the theologian David Strauss. Strauss had just recently published a work entitled The Old Faith and the New: A Confession (1872), where he attempted to explicate the loss of his Christian faith (old faith), and replace it with his newfound confidence in science (new faith). This scientific belief was not really scientific, argued Nietzsche, since Strauss demanded of the reader the same kind of awe, reverence, and worship towards the universe as one would demand of God (9). At bottom, Nietzsche thinks that Strauss wants to have his cake and eat it too. He wants the romantic “feeling of the sublime” and also wants the abolition of God in favor of the German state and German culture. One need not have faith any longer when the cosmos herself can induce piety and worship. Nietzsche quips that Strauss had simply moved from theodicy to cosmodicy. Theodicy, from Greek, was a neologism by Leibniz that combined justify and God. That is, it was a philosophical attempt to justify the existence of God. Cosmodicy, therefore, is a philosophical attempt to justify the existence of the universe. But the universe needs no justification, argues Nietzsche, and the natural scientists who work towards scientific progress should remain indifferent, since they are dealing with natural laws and not faith. “An honest natural scientist believes that the world conforms unconditionally to laws, without however asserting anything as to the ethical or intellectual value of these laws; he would regard any such assertions as the extreme anthropomorphism of a reason that has overstepped the bounds of the permitted“ (7). Ultimately, Nietzsche declares that a science that is not in service of aesthetics is unable to produce a substantive culture. “And yet what is science for at all if it has no time for culture. At least reply to this question: what is the Whence, Whither? To what end of science if it is not to lead to culture?” (8).

We congratulate ourselves for our diversity and exhort individuals to “speak their truth.” But we have no Why, Wherefore, Whence, nor Whither. There is no rhyme or reason. In an attempt to be plainer, but not pithier, allow me to elaborate. We as a culture do not know why we are here because we lack purposiveness, the gift that has been endowed, bequeathed, and vouchsafed from Being; we have no reason and therefore live in the darkness and irrationality of post-modern homelessness; we do not know from where we came because we utterly lack grounding and therefore lack a history; we possess absolutely no whither because we have no direction, orientation, procession, mission, or future—thus, we utterly lack narrative and therefore contain no τέλος, goal, or end. This is the grim landscape; this is the vacuum wherein we have attempted to construct a culture. Yet our landscape no longer contains a horizon, because of a paradigm shift that has catapulted us into a digital age with no more boundaries. Our structures built heretofore are no longer constructive because we have abolished instruction. We have therefore seen the breakdown of our body politic which, in my estimation began in the year of our Lord, two-thousand eight. If one still retains the capacity to recollect, this was the ascent of our nation’s first black president which was shortly after the release of Steve Jobs’ miracle money-maker the iPhone.

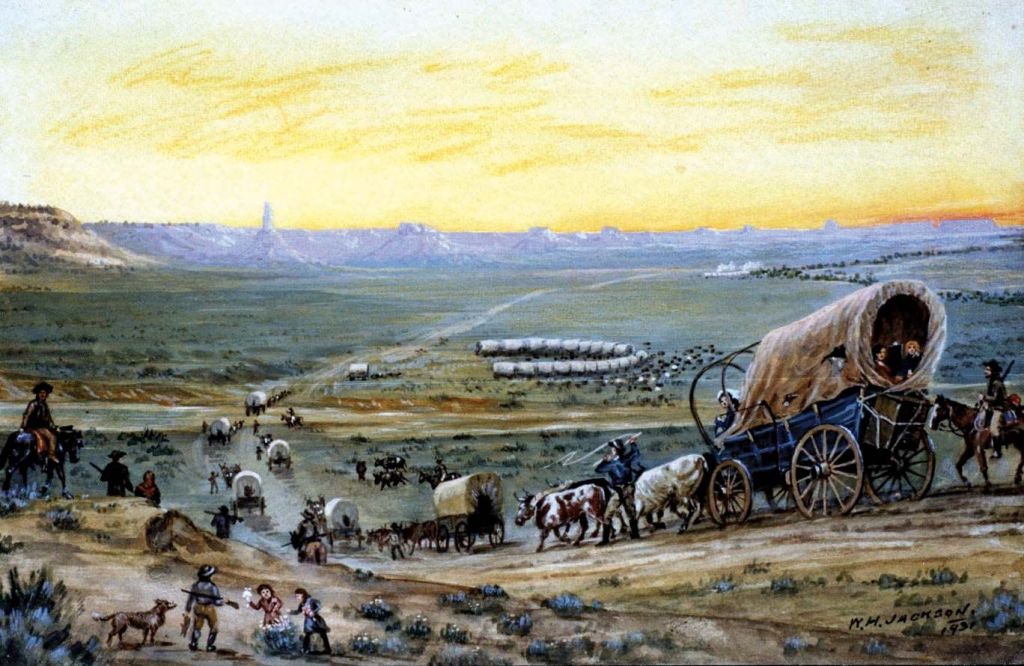

All things, however, are in a vacuum, and we receive the things we most desire and are readily at hand. More apropos, all things are not in a vacuum, but rather in a cloud. Therein they shall exist forever ever and ever, amen. All things are becoming the same, they are becoming smooth. In the absence of any negativity, or resistance, things become more homogenous and therefore more efficient. There is less diversity, complexity, and uniqueness. We as Americans, indeed, lack a cultural ethic and therefore we lack a true and substantial cultural value. We prize things like freedom, liberty, independence, and democracy, at the expense of any depth. We cannot be blamed too much, however. America lacks a cultural mythos, and therefore we do not have a shared set of ideals—neither a whence or story of origin that units us. America was founded on liberty and freedom; America was founded on Christian values; America was founded by handwork and economic opportunity; America was founded on the backs of slaves and was profitable only because of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Each story of origin tells a different history of America, a different myth indeed leads to a different destiny.

Destiny, as a concept, however, is all but nonexistent. Because destiny presupposed a telos, a fate, a goal, a holy land whereto one must pilgrimage, voyage, and venture. Today we zap back as fast as possible from point A to point B. There is no purpose to our movements because we lack a story. Thus time, which has been speeding up since the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution, has completely broken down in post-modern society. All spaces between have disappeared, for what Byung-Chul Han calls point-time or Non-Time (Un-Zeit). Any duration or space between (in today’s age of digital limitless-have-it-your-way-and-have-it-now mentality) merely causes anxiety or boredom. These are negative affects that must be “cured” by science or therapy. Thus, our culture admits no negative affectations, which has led to spiritual malaise and burnout (The Burnout Society, Byung-Chul Han). No meaning, no origin, no path, no destination, no goal—thus we have nothing to frame time (for example, the present being framed by the past and the future). “No meaning comports [verhält] time” (The Scent of Time, Byung-Chul Han, 41).

Nothing can comport time because there is no longer a framework, thus the concept of duration fades away. All things, therefore, become readily accessible, immediately. Thus memory and recollection suffer, causing conceptions of our very self to become frail, vapid, digitized—one may say, less than human. “Cheerfulness, the good conscience, the joyful deed, confidence in the future—all of them depend on a line dividing the bright and discernible from the unilluminable and dark; on one’s being just as able to forget at the right time as to remember at the right time” (Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations, 63). But there can be no dividing line in an age of unforgetfulness, where everything is eternal, limitless, and immediate. There is no Enframing (Gestell), no boundary, thus we are losing our sense of direction and our sense of self, not least our sense of culture, save for one of nonsense (pardon the pun). “The age that remembers best,” writes Kierkegaard, “but is also the most forgetful, is childhood. The more poetically one remembers, the more easily one forgets. For remembering poetically is really just an expression of forgetfulness…the whole of life moves in these two currents [of]…remembering and forgetting” (Søren Kierkegaard, Either/Or, 233, 234). Forgetting is what makes us childlike, what makes us human. Remembering is what brings back recollection, awe, longing, desire, ecstasy, fantasy, and love. No matter how hard one fights, one cannot remember and forget whilst staring at an iPad.

Since there is an absence of meaning, that is to say, no meaning conducts itself and walks with time, there is an absence of any lingering or duration. Time is immediate and present all at once. Capitalism exploits this for efficiency in order to scale up production. Politics exploits this, and takes advantage of the negative affectations that have infected society. Public opinion becomes the new truth, and all of those who have a varying ideal, value, or truth, are simply beaten into submission by the court of the people. Social media, and the compulsion to pornographically expose one’s interior life online, causes a transparency that engenders sameness. Thus, sameness extends to public opinion. In the case of academia, we see this eroding the very concept of truth and knowledge. Tenure is being viciously attacked on both sides for the sake of expediency and bureaucracy. Heidegger calls this the “dictatorship of the public realm” where the subject becomes absolutely objectified and the exploitation of the aforesaid is done principally through language. Embroiled controversies on university campuses the past decade are good examples of this playing out today. Politics, gender identity, sexuality, religion, DEI, fundamentalism, antisemitism, and immigration are just a few recent examples. “Language,” writes Heidegger, “thereby falls into the service of expediting communication along routes where objectification—the uniform accessibility of everything to everyone—branches out and disregards all limits” (Letter on Humanism, Martin Heidegger, 197). Language, which is the house of Being, the house in which mankind dwells and finds nearness to Being, devolves into a τέχνη, a modern form of technology whose goal is to speed up communication through absolute objectification.

“Haste, franticness, restlessness, nervousness, and a diffuse sense of anxiety determine today’s life” (Han, The Scent of Time, 31). Yet, we still live in expectation: not in fear of the imminent judgment of God, nor in the coming utopia that characterized the optimism of the Age of Enlightenment. Rather, with no meaning and no goal, expectation remains unfulfilled and unguided. There is no direction in which to orient oneself. Science and technology, have by and large replaced God. Thus, we both worship the Universe through our scientific pursuits, while simultaneously exploiting and objectifying every inch of the known universe in the likely event that we can procure—or dare I say, produce—our very salvation. But science, as Thomas Kuhn pointed out, is one of revolutions, and therefore not goal-oriented, rather, is cyclical. There is no “God’s eye truth” that we are close to discovering; there is no absolute or perfect knowledge. “Does it really help to imagine that there is someone full, objective, true account of nature and that the proper measure of scientific achievement is the extent to which it brings us closer to that ultimate goal? (Thomas Kuhn, Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 170). Again, Nietzsche’s question haunts us: “What is science for at all? To what end of science if it is not to lead to culture? What is the Whence, Whither?” (Untimely Meditations, 36).

We have inaugurated the age of AI which very well could lead us into a new age of morality, technology, and culture, but thus not for the better. How ought we to respond to Nietzsche’s interrogatives? From where have we come from? To where are we going? We still long for salvation in the post-modern age where we have utterly decimated the concepts of truth, knowledge, love, beauty, justice, and time. While we once held truth in esteem and lying in disrepute, AI and its hallucinations have successfully created a tertium quid. That which is a lie is presented as truth by an intelligence that knows no concept of truth or falsity. Heidegger was obsessed with the concept of Being, and spent his life’s philosophical work on trying to think of Being, knowing full well that society—even in his time—was thinking the “oblivion of Being.” What of the truth-lie of AI? Are we heading into the age of deception, a deception which confounds society and confuses culture by twisting the Whence and Whither, making us tarry with longsuffering for this “salvation through science?” I am feverish and I am sick in the soul. WWII had pockets of resistance, but this time will be different. This time we will voluntarily walk ourselves into our own oblivion, smartphone in hand.

Thus, the prophet lamented at the end of the exile of the Jews from Judah, “How lonely sits the city that once was full of people! How like a widow she has become, she that was great among the nations! She that was a princess among the provinces has become subject to forced labor. She weeps bitterly in the night, with tears on her cheeks; among all her lovers, she has no one to comfort her; all her friends have dealt treacherously with her; they have become her enemies. Judah has gone into exile with suffering” (Lamentations, 1:1-3, NRSV). I believe, at this time, all true poets and artists should redirect their work to that of the lamentation, so we can sing the woe to the death of our country–nay, our world.

Let us conclude with another lament, this time from Nietzsche:

“Lament—It is perhaps the advantages of our times that bring with them a decline and occasional underestimation of the vita contemplativa. But one must admit to himself that our age is poor in great moralists, that Pascal, Epictetus, Seneca, and Plutarch are now read but little, that work and industry (formerly attending the great goddess Health) sometimes seem to rage like a disease. Because there is no time for thinking, and no rest in thinking, we no longer weigh divergent views: we are content to hate them. With the tremendous acceleration of life, we grow accustomed to using our mind and eye for seeing and judging incompletely or incorrectly, and all men are like travelers who get to know a land and its people from the train. An independent and cautious scientific attitude is almost thought to be a kind of madness: the free spirit is brought into disrepute, particularly by scholars who miss their own thoroughness and antlike industry in his talent for observation, and would gladly confine him to a single corner of science; while he has the quite different and higher task of commanding the entire arrière-ban of scientific and learned men from his remote outpost, and showing them the ways and ends of culture. A lament like this one just sung—will probably have its day and, at some time when the genius of meditation makes a powerful return, cease of itself” (Nietzsche, Human All Too Human, V, 282).

Discover more from Blessed are the Poor in Spirit

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.