Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus. New York: Vintage International, 2018, 160 pp. $16.00

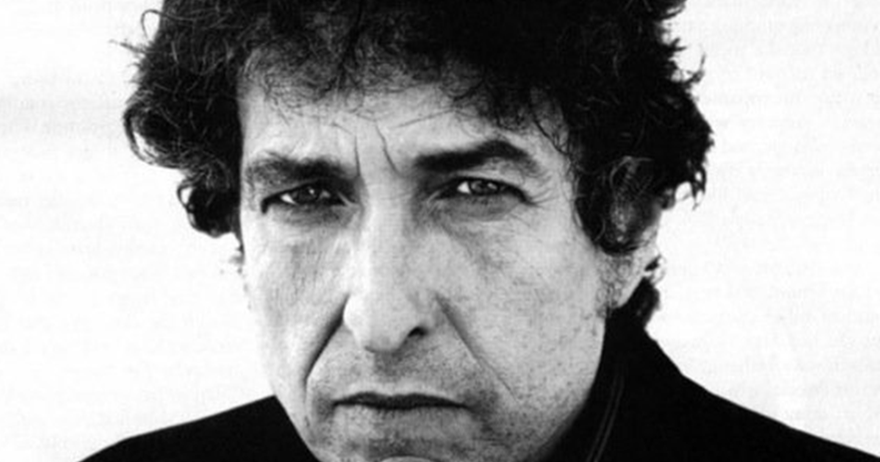

“All my loyal and my much-loved companions, they approve of me and share my code,” sings Bob Dylan in “Ain’t Talking” from his 2006 album Modern Times. “I practice a faith that’s been long abandoned, ain’t no altars on this long and lonesome road.” Bob Dylan sings of the absurd. He writes of a world that has long been abandoned by God, the original “gardener of Eden.” He sings of this world; this world that is imbibed with suffering and of an existence riddled with chaos and meaninglessness. He is “on the road” (in fact, Bob Dylan has been on his “never-ending tour” since 1988) walking…conscious that there are no alters on which to sacrifice.

Indeed, there are no gods needing propitiation nor men needing expiation. There is only unending suffering “in the last outback, at the world’s end” (c.f. Ovid, Ex Ponto, 2.7.66). Dylan rounds out the refrain crooning: “Ain’t talkin’, just a-walkin’, carryin’ a dead man’s shield. Heart burnin’, still yearnin’ A’walkin’ a’with a toothache in my heel.” The ancient Spartans had a code of honor to fight unto the death, for to flee would have brought great shame on yourself and your family back home. Thus, the saying ascribed to Plutarch, ἢ τὰν ἢ ἐπὶ τᾶς ([come back home] either with [your shield] or on it).

What Dylan is describing is nothing less than the absurd reality of a godless existence. The warrior has been slain, and his shield, both as a representation of his life and his guilt, travels on with the walker. Yet this march is not liberating and brings no freedom. It is an unending journey that contains an unbearable nagging, an annoying throbbing, and a persistent pain that “shall never pass.” This is the same “toothache in my heel,” that crazy “Old Dan Tucker” had, an antebellum Southern folk song published by Dan Emmett in 1843. The song most likely arose from an earlier slave song about an escaped slave from Tennessee; or, perhaps, a part-time Southern minister from Elberton, Georgia. Old Dan Tucker “is a fine old man” who washes “his face with a frying pan.” He combs “his hair with a wagon wheel” and ultimately dies because of a “toothache in his heel.” The refrain of the song codifies the absurdity of the life of Old Dan: “Get out the way Old Dan Tucker, you’re too late to git your supper. Supper’s gone and dinner’s cookin’ Old Dan Tucker’s just a-standin’ there lookin’.” Or in other words, “He that is unjust, let him be unjust still: and he which is filthy, let him be filthy still” (Revelation 22:11, KJV).

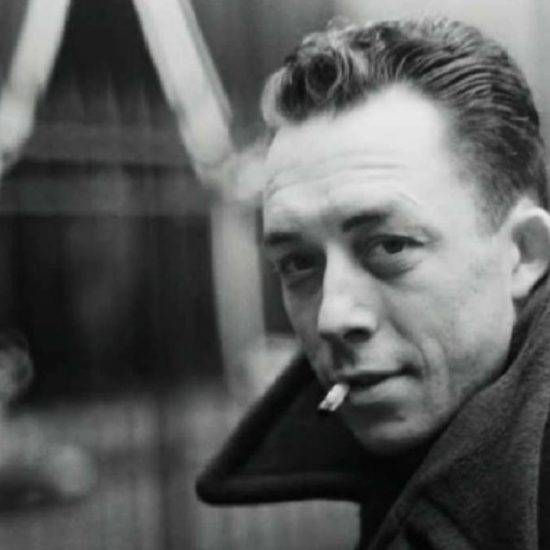

The Myth of Sisyphus, by French-Algerian author and philosopher Albert Camus, was published in 1942 in the middle of World War II, a world that is markedly different, but not altogether dissimilar, from our global landscape in 2024. In the work, Camus aims to answer the question of whether or not suicide is a legitimate response to a godless world. “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem. And that is suicide” (3). In answering this question, he puts forth his absurdist philosophy which truly is a maximalist modus vivendi. The book itself is divided into three main sections with a short conclusion and an appendix. In the first part (An Absurd Reasoning), Camus argues for the absurdity of the world and concludes that suicide is not a legitimate response to this absurdity. There is interaction with both Husserl and Kierkegaard. In the second section (The Absurd Man), he explores different ways in which the absurd man could be represented; viz., in Don Juan, the Dramatist, and the Conqueror. In the final section (Absurd Creation), he explores the absurd man as a creator, through both philosophy and literature, examining protagonists in novels by Dostoyevsky and Kafka. He concludes with a brief recapitulation through the Greek myth of Sisyphus, a man condemned by the gods to roll of rock up a hill forever. “The night has no end, he is still on the go. The rock is still rolling,” writes Camus impudently, “[but] one must imagine Sisyphus happy” (123).

The absurd man is only interested in the pure flame of life

Camus’s absurdist philosophy is not for the faint of heart. To be sure, his philosophy is defined as “an unceasing struggle” ending only in death (31). This is not the existentialist humanism of his fellow Frenchman, Jean-Paul Sartre. No; Camus’s philosophy of the absurd transforms “what once was an invitation to death” into a new regula of revolt, passion, and freedom (64). Contra Sartre’s existentialism, the absurd philosophy of Camus does not create subjects who are “condemned to be free” or individuals with “radical freedom.” For Camus, the absurd man doesn’t care whether any sort of metaphysical freedom exists—for they exist in a perpetual state of indifference or what Camus terms, without appeal. “Knowing whether or not man is free doesn’t interest me” retorts Camus, “The problem of ‘freedom as such’ has no meaning. For it is linked in quite a different way with the problem of God” (56). Camus saw the existence of God less of a problem with freedom and more of a problem of evil. The reality is that for one thousand five-hundred years, Christian theology grappled with the inextricable dogmas of God’s omniscience, will, and human freedom. Reconciling the existence of God and evil (theodicy) really takes hold post-Descartes, for example in Leibniz and Hume. Although theologians with deterministic systems had to grapple more with the theodicy problem because of specious doctrines of free-will, like Calvin or Augustine, the logical problem of evil goes back at least to Sextus Empiricus, Epicurus, or even Socrates in Plato’s Euthyphro. Thus, Camus concludes resolutely, “What freedom can exist in the fullest sense without assurance of eternity? …Thus the absurd man realizes that he was not really free” (57, 58).

For the absurd man is only interested in the “pure flame of life. [For] it is clear that death and the absurd are here the principles of the only reasonable freedom: that which a human heart can experience and live” (60). They live in the here-and-now and are consumed, or more accurately, they consume all that the physical world has to offer. This is the only kind of freedom in which the absurd man operates. This absurd universe offers no preferences, no values, and no meaning. Therefore, the absurd man ought to live in a continual state of “indifference to the future and [with] a desire to use up everything that is given” (60). This is not Seneca’s happy life of Stoic virtue; neither is it Epicurus’ good life of austere “hedonism.” The absurd man struggles and seeks quantity over quality. Camus does not shy away from this conclusion and states it thus: “But what does life mean in such a universe? …belief in the absurd is tantamount to substituting the quantity of life experiences for the quality…A man’s rule of conduct and his scale of values have no meaning except through the quantity and variety of experiences he has been in a position to accumulate” (61, 61, emphasis mine). The absurd man’s entire life is marked by revolt, indifference, and lucidity in the face of the ephemeral. The absurdist individual gives nothing to the eternal and rests on no a priori principles. “No code of ethics and no effort are justifiable a priori in the face of the cruel mathematics that command our condition” (16). To be sure, all things are “equivalent” in the absence of a value system: “Where lucidity dominates. The scale of values becomes useless (63).

When Camus speaks of not resting on the eternal, he simultaneously is critiquing rationalism and irrationalism. We need not say anything else about the former since it is self-explanatory given Camus’s anti-rational stance of his absurdist philosophy (contra Descartes, Leibniz, Kant, Hegel, etc.). But for the latter, it is both the religious and irreligious stripes he protests against. For the religious irrationalist philosopher, like Kierkegaard, there is a “leap to faith” in spite of the absurd (pp. 33-41). Camus offers his interpretation as follows, “Kierkegaard likewise takes the leap. His childhood having been so frightened by Christianity, he ultimately returns to its harshest aspect. For him, too, antinomy and paradox become criteria of the religious” (37). Neither in atheistic phenomenology nor Christian mysticism should one take this “leap.” Indeed, Camus sees both as two sides of the same coin. He accuses Husserl of denigrating the power of reason only to leap to “Eternal Reason” (46) which he sees as no different than Platonism. Camus accuses philosophers of the irrational as inconsistent since their desire to “understand” and seek an explanation overrides their system. So, there is a making space and a giving way. “Nostalgia is stronger than knowledge,” quips Camus (48). This “nostalgia” is a type of longing, which influences philosophers towards either extreme rationalization and division of the world, or in the extreme Irrationalization, from which Camus accuses existentialist philosophers of the deification of the irrational” (48).

The absurd man claims no masters of his destiny save himself. “It is good for a man to judge himself occasionally. He is alone in being able to do so” (65). For he has shattered all illusions and any hope for the promised land, a homecoming, or a return to Eden is rejected. This absurd is a philosophy of hopelessness, or to be more precise, “the absurd is sin without God” (40). The absurd man therefore stands as “the [exact] contrary to the reconciled man” (59n2). The absurd, at its essence, thereby becomes god (Kierkegaard, Deleuze, Kafka) (48-49). Camus calls this leap back to the eternal “philosophical suicide” and also sees it as illegitimate. He writes, “[this] final leap restores in him the eternal and its comfort. The leap does not represent an extreme danger as Kierkegaard would like it to do. The danger, on the contrary, lies in the subtle instant that precedes the leap. Being able to remain on that dizzying crest—that is integrity and the rest is subterfuge” (50, emphasis mine). Actual suicide, like philosophical suicide, is, for Camus, still a leap into the eternal. He therefore rejects it because one bows to the eternal; one succumbs to it, and therefore gives it legitimacy, which is contrary to its nature. He clarifies, “Suicide, like the leap [to the eternal], is acceptance at its extreme…In a way suicide settles the absurd…the contrary of suicide, in fact, is the man condemned to death” (55). The condemned man does not accept his fate, however. On the contrary, he revolts to the bitter end.

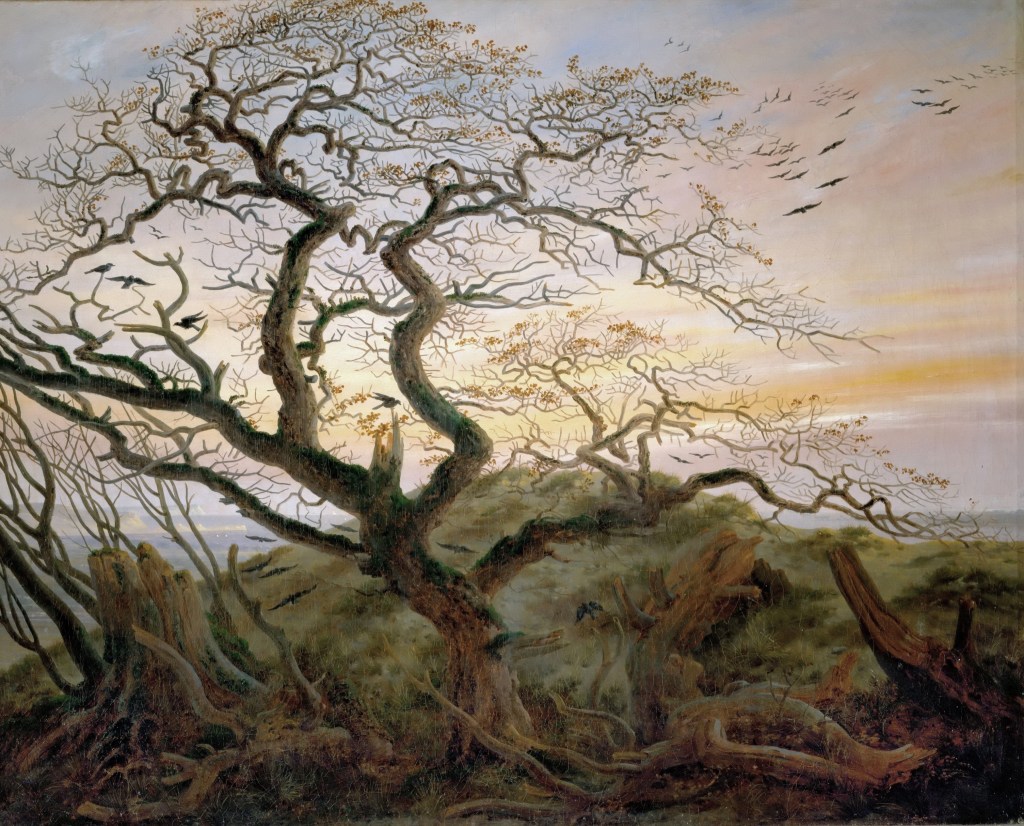

Even science, for Camus, is a fruitless endeavor because life itself lacks an explanation. For Camus, the only thing that exists, to be sure, is the flesh or sensible world. “This is the world I can touch, and I likewise judge that it exists. There ends all my knowledge, and the rest is construction” (19). But this world is chaotic, absurd, and meaningless, and cannot be dominated and certainly cannot be comprehended. Indeed, for Camus, science does not even enable the disjunctive subject to apprehended the world since it merely hypothesizes: “I realize that if through science I can seize phenomena and enumerate them, I cannot, for all that, apprehend the world” (20). Indeed, for Camus there is still a residual Cartesian disjunction between mind and the material universe. For it is consciousness that has plagued mankind to suffer under the burden of the absurd, that has set mankind up in opposition to this absurdity and chained him thereto until all men meet their ineluctable fate in death. “There can be no absurd outside the human mind,” writes Camus, “the absurd ends with death. But there can be no absurd outside this world either…[For] a man who has become conscious of the absurd is forever bound to it” (30, 31). Camus concludes, “All is chaos, all that man has is his lucidity and his definite knowledge of the walls surrounding him…man stands face to face with the irrational. He feels the longing for happiness and for reason. The absurd is born of this confrontation between the human need and the unreasonable silence of the world” (27, 28). Forsooth, and this silence is deafening.

Camus does, however, offer to us a few suggestions that might allow the absurdist individual to live a more lucid life and be closer and more in touch with his naked and bare self. They are first explored through three profiles which are the (1) seducer, (2) the conqueror, and (3) dramatist. The “Don Juan” type achieves lucidity through his indifference in romantic or sexual relationships. He does not grow attached, holds no illusions, and gains a knowing through “loving and possessing” (75). The conqueror achieves lucidity through vanquishing and overcoming—principally the overcoming of oneself and of God. “Man is his own end. And he is his only end. If he aims to be something, it is in this life” (88).

Contra Sartre, who specifically stated that mankind was not his own end, so as to avoid the deification of man in the utilitarianism of John Stuart Mill or the positivism of Auguste Comte, Camus chooses man and man alone. “For the path of struggle leads me to the flesh…even humiliated, the flesh is my only certainty” (87). But in contradistinction to the aforesaid philosophers, Camus is no altruist, and humanity has no goal to achieve, neither a greater good to pursue. Lastly, he profiles the dramatist who he sees as the consummate artist, one who “mime[s] the ephemeral” and converts all things “into flesh” (80). For Camus, we are all faced with this choice: the eternal [God] or oneself, and it is simply the play actor who leers intrepidly at this fork in the road and traverses the latter over the former. No talking, just walking, over the apocalyptic ruins of the universe which is destroyed and rebuilt each day anew: This is the tragedy of existence. In former times, theatre actors, playwriters, and dramatists were the scandalous ones; the ones whom the church would excommunicate. In effect, “entering the profession amounted to choosing Hell” (83). Molière, for example, died on stage in his costume and makeup. As he was dying, he was denied his last rites by two clergymen. “To the actor as to the absurd man,” writes Camus, “a premature death is irreparable” (83).

We therefore are left with Duan Juan (seduction), Napoleon (conquest), and King Lear (tragedy) in the face of the absurd. And while Molière preferred tragedies, he became famous for his comedic genius and his farces. While comedy and tragedy are both integral to the dramatic experience, when one removes the masks, tragedy leaves a melancholic man, who attempts to engender mawkish sympathy for his plight. This works in part, but only temporarily—for we are all stewing in the same generational pot beneath the sky (Baudelaire). The melancholic man, therefore, lacks an established sense of revolt that is necessary to live in the face of the absurd. Therefore, he must turn his suffering into laughter. “But in order to endure this this type of extreme pessimism and to live alone ‘without God and morality’ I had to invent a counterpart for myself,” bellows Nietzsche. “Perhaps I know best why man alone laughs: he alone suffers so deeply that he had to invent laughter. The unhappiest and most melancholy animal is, as fitting, the most cheerful” (Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power, 1.91).

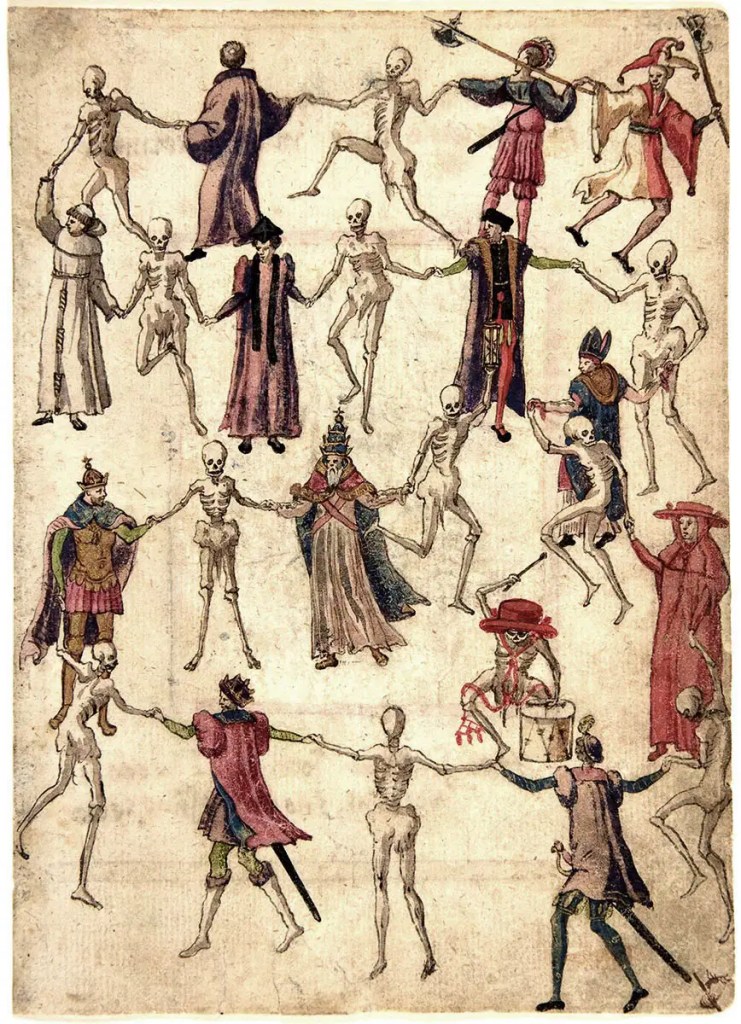

In light of this, it would behoove us to postulate an additional profile into Camus’s conception of the absurd man: the court jester. Contra the dramatist who “will die in three hours under the mask he has assumed today…travel[ing] the whole course of the dead-end path that the man in the audience takes a lifetime to cover” (80), the court-jester puts on no mask and assumes no role. No; his indifference is much more subtle, artful, and curated. The court jester retains a level of lucidity, navigating the world vis-à-vis the absurd in an exercise of comedic showmanship, mystery, deception, and skill…and the court laughs. The great silent movie film stars are examples of this: Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and Fatty Arbuckle. Chaplin quipped that: “laughter is the tonic for pain.” Harry Houdini (a business partner of Buster Keaton’s father) and P. T. Barnum are also excellent examples of the absurdist court jester. Groucho Marx, likewise, represents the absurd funnyman who lived “without appeal” using comedy as his vehicle of art. “I intend to live forever, or die trying,” deadpanned Marx. The absurd man might be a condemned man, but he is not a resigned man. Like Prometheus, the original insurrectionist against the gods, he must revolt unto the bitter end, laughing to his grave.

So, what of Old Dan Tucker who is late for supper? Dan Tucker represents the fool that was transformed into the absurdist sage. “Over time Dan Tucker shape-shifted…Dan Tucker was [originally] pictured as a vagabond Negro who was laughed at and scorned by his own kind but who constantly bobbed up among them with outrageous small adventures…Get out the way Old Dan Tucker? I’m not going anywhere…Who says I ain’t president? Nobody can stop me. And that’s who’s walking through [Bob Dylan’s] ‘Ain’t Talkin’” (Greil Marcus, Folk Music, 147, 148). Without a doubt, Camus’s absurd man must continue to walk, toothache in heel. He marches stolidly, stoically, and serenely, over the dead embers of bygone eras. Notwithstanding the glaring absence of value, meaning, or hope, he rebelliously walks to the beating drum of his funeral march. Only death awaits him. His only tools are revolt, freedom, diversity, and passion (117). He must create, but there is no purposiveness to his creation. For the artist can create and then in an iconoclastic fury, destroy his very creation the next day—that too is equivalent. “Detached from it [creation], the work will once more give a barely muffled voice to a soul forever freed from hope. Or it will give voice to nothing if the creator, tired of his activity, intends to turn away” (116). The absurd man has no hope, he is condemned, but he has “smug thought[s]” and “scorn”; indeed, Camus defiantly concludes, “there is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn” (116, 121).

“There always comes a time when one must choose between contemplation and action,” challenges Camus: There is a God or time, that cross or this sword. This world has a higher meaning that transcends its worries, or nothing is true but those worries. One must live with time and die with it, or else elude it for a greater life. I know that one can compromise and live in the world while believing in the eternal. That is called accepting. But I loathe this term and [I] want all or nothing (86).

Reading Camus is intoxicating. One feels drunk, ecstatic, and otherworldly.

The philosophy of Camus is both dizzying and alluring; confusing yet beguiling; nauseating and enchanting. Camus stands as a great tempter, enticing us to live in a hopeless world on this dizzying crest, razor’s edge, precipice of the cliff, and stare lucidly but to make no leaps to safety. In Camus’s world, you wake up in an undisclosed location, groggy, unsure if how you got there or wherefore. You hear the sound of a revolver cylinder clicking as it spins which is thereupon locked into place and violently foisted into your hand. A phantasmagoric specter looms over you and engulfs you in feelings of despair, hopelessness, and anxiety. A wave of metaphysical nausea washes over you. Your mind is racing yet your body freezes as in sleep paralysis. Are you awake or asleep? “Shoot” commands the demon. There is no alternative: you raise the revolver to your temple and pull the trigger…click. The chamber was empty! Overwhelmed with relief, you sigh and collapse exhaustedly back onto the bed. Immediately, however, the phantasm forces you to get up, and leads you down a dark spiraled staircase into a strange, wet, and moldy cellar. You are subsequently hung to death in the gallows. No one hears your screams and there is no one to offer you mercy—metaphysically, mercy does not exist. There is no future: the only thing that is real are your fears. “The absurd godless world is, then,” declares Camus, “peopled with men who think clearly and have ceased to hope” (92).

Reading Camus is intoxicating. Like the Green Fairy of Rimbaud and Verlaine, one feels drunk, ecstatic, and otherworldly imbibing on absinthe in a whirlwind of productivity, pleasure, and creativity. This is the lucidity and revolt of Camus—the choosing of Hell. But eventually the Green Fairy was shelved by Rimbaud; after all, his infamous poem A Season in Hell, is explicit—the nightmare is only for a season. The death of Molière the consummate dramatist, who died wearing green, led to a superstition that all good actors know: don’t wear green on stage or else invite bad luck. “These images do not propose moral codes and involve no judgments,” writes Camus, “they merely represent a style of life…let me repeat. None of this has any real meaning” (90, 117). In sum, The Myth of Sisyphus invites the reader into a philosophy of meaninglessness and hopelessness; it is a seductive invitation to bite the bullet in the face of the absurd by putting on green vestments and rebelling against a “fate that is fatal” (117). I, for one, resolutely refuse to rebel against this fatality. Like King Oedipus in the Sophoclean tragedy, all rebellion—no matter how scornful, desperate, or impassioned—seals thy fate. For the others, however, whether they wish to remain on the “dizzying crest” I care not; but as for myself, I shall take the leap into the eternal every time.

Discover more from Blessed are the Poor in Spirit

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.