(The Death of God, Post-Modernity, and the Poet’s Task)

Meet the Beatles

In March of 1966, John Lennon infamously deadpanned that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus. Afterwards, the Fab Four were, naturally, excoriated by the press—especially in the American South. However, outrage wasn’t contained even to America, as individuals on at least three different continents added additional clamorous outrage to the already present cacophony. Fans swarmed together like enraged hornets, mobilized by the indignation of the conservative radio stations, to publicly burn records in a show of defiant rejection. Indeed, radio stations blacklisted the Beatles and refused to play their music. Shows for their subsequent 1966 US tour were picketed by the Ku Klux Klan. Whether or not Lennon’s remark was true or not was irrelevant to the uproar. Lennon, after all, was simply stating the truth—both as a sociological critique to the declining interest in religion in the mid 1960s, and, secondarily, to the fact that Jesus, after all, only had twelve followers himself. Lennon, ultimately, lost some followers that day because of this hard saying. Thankfully, he didn’t have Twitter.

Jesus himself would also lose some followers when he retorted that anyone serious about gaining eternal life should “eat his flesh and drink his blood.” “On hearing it, many of his disciples said, ‘This is a hard teaching. Who can accept it?’ Aware that his disciples were grumbling about this, Jesus said to them, ‘Does this offend you?’” (John 6:60-61). Well, it certainly offended more than a few people—so much so that they put Jesus to death. Indeed, Lennon’s word’s offended at least one individual as well, Mark David Chapman, who on his own admission, said Lennon’s remarks were at least partially responsible for his motivation to assassinate Lennon in 1980 outside his home in NYC.

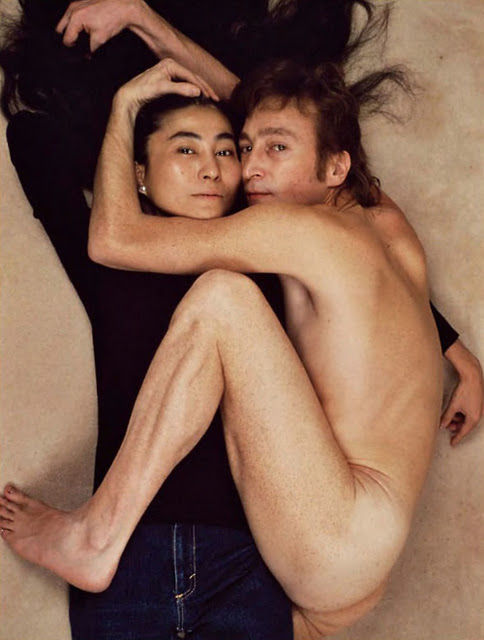

“I don’t believe in Bible. I don’t believe in Jesus,” Lennon poignantly sings in “God” off of his 1970 John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, “I just believe in me. Yoko and Me.” Chapman, who likened himself to be a “phony killer” in the similitude of Holden Caulfield, saw Lennon as the paragon of phoniness. For how could one sing: “imagine no possessions,” or, “all you need is love,” while rolling around in luxury and ostentation? In the exasperated and angsty words of Holden himself: “If you sat around there long enough and heard all the phonies applauding and all, you got to hate everybody in the world…I said old Jesus probably would’ve puked if He could see it—all those fancy costumes and all. Sally said I was a sacrilegious atheist. I probably am.” (The Catcher in the Rye). Whether Chapman was insane (for he ultimately refused to plead insanity while on trial) or not doesn’t belie that he was in fact sincere in his beliefs, however troubled his mind was. However, sincerity alone, as moral philosopher Harry Frankfurt points out, is, to be sure, the ultimate form of bullshit. Jesting Pontius Pilate echoes the selfsame sentiment before he flexes his political muscles and sends the pesky insurrectionist Jesus to his death: “What is truth?” he shrugs (John 18:38).

“For it is the job of the æsthete—the poet, the musician, the painter—to find beauty wheresoever she may deign to lay her head”

In Search of Hyperborea

Truth cannot be divorced from reality; truth is not something that is merely sincerely believed. The world of the poet can no longer be described in vivid, Edenic, Shakespearean imagery of “reclining ‘neath the bower.” By the advent of Keats, this type of Romanticism already had begun to feel nostalgic, and it’s no marvel that the Romantics hearkened back to Ancient Greece and Rome to capture the idyllic era of yesteryear in mesmerizing verse. For the simplicity and light would soon set, and a new darkness would cast her hypnotic shadows on the world: Novalis’ Hymn to the Night was, in this respect, prescient and, like many-a-poet before him, before its time. “Away I turn the holy, the unspeakable, the secretive Night. Down over there, far, lies the world—sunken in a deep vault—its place wasted and lonely. In the heart’s strings, deep sadness blows…Should [Light] never come back to Its children, who are waiting for it with simple faith?” (von Hardenberg, Hymnen an die Nacht, I).

By the time of the Industrial Revolution, you had Transcendentalists, greatly influenced by the Romanticism and Idealism philosophy of Europe, building cabins in wealthy patron’s backyards and writing books called Life in the Woods. Jokes aside, one should be cautious about slinging the hypocrisy charge too hard against Henry David Thoreau. Building a cabin by hand is still way more badass than filming a “nature walk” in your backyard for your TikTok. As Seneca lampooned his detractors who stated he couldn’t be living a virtuous and philosophic life because of his wealth: “I am an athlete by comparison [to you all]” (On the Happy Life). Or, in other words, “don’t point your damn finger at me, at least I’m trying!” Sure, Lennon’s net worth was upwards of $200 million (roughly $700 million in today’s dollar) at the time of his death, but…at least he was trying. By comparison, Mark David Chapman was an alcoholic, a security guard, and college dropout.

For it is the job of the æsthete—the poet, the musician, the painter—to find beauty wheresoever she may deign to lay her head; uncover truth wheresoever she may hide; and dance with reality, no matter how gruesome, grim, or ghastly. Alexander Scriabin, the Russian romantic composer who saw Art as the way to elevate the consciousness of humanity to a higher transcendental state, once declared “I am God! I am nothing, I’m play, I am freedom, I am life. I am the boundary, I am the peak.” Anyone, indeed, who has chanced to hear his Op. 54, Le Poème de l’extase, can adjudicate for herself whether or not this statement was made in good faith. Scriabin’s Op. 26, Symphony No. 1, is a mighty, monumental, and masterful orchestral opus with six movements, completed in the year 1900. The final movement, which includes a chorus, is a paean to the sovereignty of Art: “O highest symbol of Divinity, Supreme Art and Harmony, we bring praise as tribute before You…In the exhausted and afflicted mind you breed thoughts of a new order. Come, all peoples of the world, Let us sing the praises of Art! Glory to Art, Glory forever!”

As the demons of old were cast out and forced to travel through dry places, seeking another body to inhabit (Matthew 12:43), so too must the poet make liberal use of the mask, like the ancient Greek dramatists. Charles Baudelaire explicates, “The poet enjoys the incomparable privilege of being able to be himself or someone else, as he chooses. Like those wandering souls who go looking for a body, he enters as he likes into each man’s personality” (Crowds). Whitman also declared, “Do I contradict myself? Very well then, I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes.” Arthur Rimbaud too, “Je est un autre.”

“If that age could come again, that age gone by! For Man is finished! Man has played his roles! Now in daylight, tired of smashing idols, He will arise again, freed from his Gods, And, child of heaven, will contemplate the skies! Ideal, invincible, eternal Thought, the god within, beneath his mortal clay, Will then arise, will shine upon his brow! Arise, and cast upon the Universe Infinity of Love in Love’s infinite smile! The World will resound like some vast lyre that trembles in some endless vast embrace. The world thirsts after love: you will assuage it!” (Rimbaud, Credo In Unam, III). We mortal clay have arisen, forsooth!, we have puffed our chest and stood tall. “Nay but, O man, who art thou that repliest against God? Shall the thing formed say to him that formed it, Why hast thou made me thus? Hath not the potter power over the clay, of the same lump to make one vessel unto honour, and another unto dishonour? (Rom 9:20-21).

“The poet needs become a pulchri et veri creator, an Author, nay, a god, of Beauty and of Truth, no matter how painful, violent, or harsh the creation process might be.”

And we have done just that. Proudly, we have stripped God, that bastard, of all power, and shattered our idols in an apoplectic fury of rage and regret. As Nietzsche foresaw and bemused, “With regard to the cross-examining of idols, this time it is not the idols of the age but eternal idols which are here struck with a hammer as with a tuning fork—there are certainly no idols which are older, more convinced, and more inflated. Neither are there any more hollow. This does not alter the fact that they are believed in more than any others, besides they are never called idols—at least, not the most exalted among their number” (Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols).

The Death of God & the Task of the Poet

“We are the hollow men” wrote T.S. Eliot, “we are the stuffed men…This is the way the world ends, not with a bang but a whimper” (The Hollow Men). Post-modernity has since usurped modernity in a coup de grâce, whereby both god and humanity have become utterly vacant, stuffed up with straw like a scarecrow. Life has become base, raw, naked, and as flat as a pancake (Byung-Chul Han). In the absence of truth, meta-narrative, she is a sailor, floating in the never-ending sea of time, simply waiting to crash upon the shore of eternity. Do we yet contemplate the sky? Indeed, stripped of all majesty and mystery, it has become, as Baudelaire wrote, “the black lid of the mighty pot, where the vast human generations boil!”

The poet once was a discoverer of beauty and truth. She was the passive, curious observer of the mystical, mythical, recondite realities that only sages could peer into. Now, however, the poet can no longer sit passively—dare one say idly—by the wayside and expect Beauty to attend to her “’neath the bower.” “The world is evil; Does that surprise you? Live; to the fire” (Rimbaud, The Triumph of Patience). “I’ve seen the arrow on the doorpost saying this land is condemned, all the way from New Orleans to Jerusalem. God is in His heaven and we all want what’s His. But power and greed and corruptible seed seem to be all that there is” (Bob Dylan, Blind Willie McTell). But God is no longer in his heaven, and the world is in the constant struggle for the will to power. The poet, like the prophet, is “not without honor except in his own country” (Mark 6:4). Except the poet’s own country is his generation, and therefore, more often than not, it has been her lot to die in the gutter, be buried in an unmarked grave, and to be forgotten by the vicissitudes of time. Thus does Dylan melancholically ring the chimes of freedom for the unknown artists who came before their time, singing: “Striking for the gentle, striking for the kind, striking for the guardians and the protectors of the mind, and the poet and the painter far behind his rightful time, and we gaze upon the chimes of freedom flashing” (Chimes of Freedom). The poet needs become a pulchri et veri creator, an Author, nay, a god, of Beauty and of Truth, no matter how painful, violent, or harsh the creation process might be.

Charles Baudelaire recalled his encounter with a glass-maker where he was suddenly overcome with an arbitrary, violent, madness of spirit: “What! You have no colored glass? No pink, no red, no blue? No magic panes? No panes of paradise? Scoundrel,” whereupon he picked up some of the gentleman’s merchandise and forthwith began hurling the glass from the balcony, like a demoniac, down upon his head. “Drunk with my madness, I shouted down at him furiously: make life beautiful! Make life beautiful! [For] what is an eternity of damnation compared to an infinity of pleasure in a single second?” (The Bad Glazier).

Conclusion

Ever and anon a special soul shall burst through a generation as a blazing comet does through the pitch of the night. Ignited by the love and truth of Apollo, filled with the Furies, inspired by the Muses, and enchanted by the dithyrambs of Dionysus, the poet will leave an indelible mark on the consciousness of humanity. Then, almost as quickly as she appeared, she will die, and her body will return to the earth whence she came. “Great writers are indecent people they live unfairly saving the best part for paper. good human beings save the world so that bastards like me can keep creating art, become immortal. if you read this after I am dead it means I made it” (Charles Bukowski). If we are resigned to the back pages, we accept our lot stolidly and placidly, for life is sufficient unto itself.

Discover more from Blessed are the Poor in Spirit

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.