Last month I was in the worst car crash of my life. In fact, it was the only real car crash that I have been in, save a minor fender bender back in 2013. Although I pride myself in being a great driver (and let it be known to the world, that I am), this does not change the fact that other drivers are bad drivers. Or to be specific, it does not prevent seventy-five-year-old grandmas from ripping past a stop sign at forty miles an hour and crashing into your passenger side door, when you clearly had the right of way. More generally and universally: no matter how well you live life and take caution, very bad things inevitably will happen to you. And again, you cannot control the actions of others. Very well.

As a six on the enneagram, I am driven by fear and anxiety, a sort of l’angoisse de la vie, that causes me to plan for catastrophes and worst-case scenarios (Epictetus would approve! c.f. Discourses, 3.8). And yet, it also has prepared me to spring into action when something terrible does happen. Another poignant example of this was the apartment fire that my ex-wife and I had nine years ago. Anyway, within twenty-four hours after the accident, I had hired an attorney, got a rental car, scheduled x-rays, booked the intake at both the doctor and chiropractor, filed the accident and the bodily injury claim, and started research in order to secure a new car. Nevertheless, the accident itself was jolting, if not harrowing.

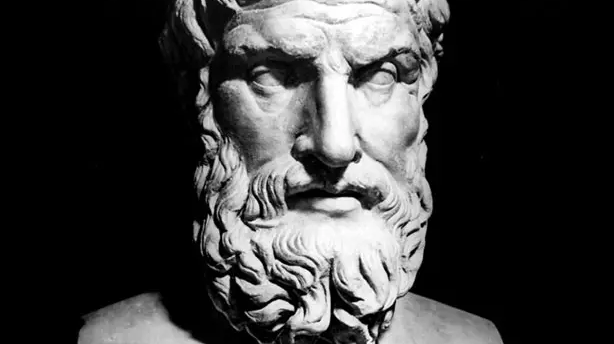

In my philosophy group we recently have been studying Stoicism. Last month we read through Epictetus’ Enchiridion and The Discourses. This month we are reading through Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations (next month Seneca!). I have always had an affinity for Stoicism. This probably has to do with my penchant for philosophies that could be considered austere, extreme, or radical (i.e., asceticism, monasticism, existentialism, nihilism). My studies of the ante-Nicene church fathers like Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, and Origin deepened my appreciation for the philosophy, as I saw the way it influenced and was appropriated by these early theologians, even if I didn’t agree with their conclusions (i.e., Tertullian arguing for the corporeal nature of the soul; Clement arguing that Jesus was akin to the stoic sage and was perfectly ἀπαθής while on earth, even during his passion, pun intended!). More specifically, I’ve appreciated the idea of non-attachment, which has many parallels in Buddhism, and the idea of living in accordance to nature, which has many parallels in Taoism. Even still, there are parts of the stoic doctrine that I was able to criticize in my mind cogently this time around that I was not able to do for myself when I first read through these texts ten years ago. For better or for worse, or, more apropos, believe it or not!, it was Stoicism I was thinking about while being t-boned by a Nissan Rogue hatchback, which precipitated a whole host of human, all-too-human emotions from the wellspring of my soul.

The Stoic Thought of Marcus Aurelius & Epictetus

In Stoic thought, mankind is unique in that he possesses reason (ratio); indeed, it’s these λόγοι in all men that allow us to share and participate in the divine being, which is good (Discourses, 2.8.1-2). This reason gives us the ability to make judgments for all external things. Man is, as it were, the sole captain of his ship. “I refuse as this is up to me. I will put you in chains. What’s that you say, friend? It’s only my leg you will chain, not even God can conquer my will” (Discourses, 1.1.23-24). And yet, all things go according to nature, which is not evil, it just is. Even the random occurrences and happenings all have a rational order and logical flow because of the λόγος σπερματικός in all things. “What comes after is always in affinity to what went before. Not some simple enumeration of disparate things and a merely necessary sequence, but a rational connection: and just as existing things are harmoniously interconnected, so the processes of becoming exhibit no mere succession, but a wonderfully inherent affinity” (Meditations, 4.45). As Epictetus puts it, “You carry the living God inside of you (Discourses, 2.8.13).

Everyone, therefore, has within themselves the autonomy and power to endure anything, and not just to endure it, but to love it in gratitude and thankfulness. “You sit crying and complaining – some of you blind to your benefactor, and unable to acknowledge his existence; others assailing God with complaints and accusations from sheer meanness of spirit. I am prepared to show you that you have resources and a character naturally strong and resilient; show me in return what grounds you have for being peevish and malcontent” (Discourses 1.6.42-43). Or as Marcus more succinctly put it, “Universal nature has brought you nothing you can’t endure”(Meditations, 8.46).

All things that are outside of the self-directed mind are simply φαντασίαι, or impressions. These impressions include all external stimuli, but also internal pre-cognitive judgments that are the result of our preconditions, presuppositions, life circumstances, or even subconscious thinking. They would all be considered externals because they are not “up to us,” and therefore outside of our control. Internals, or things in our control, are simply our judgments, which would include our will, desire, actions, or the mental faculties more generally. The ultimate goal of the stoic is virtue, which is gained through things like truth, justice, and wisdom, with philosophy of course being only vehicle whereby one can achieve this. All other things, unless they are considered bad (re: evil, an action not according to nature or done for the common good, i.e. the Epicureans making pleasure and avoidance of pain their ultimate goal!), are matters of indifference, or ἀδιάφορα. So whether someone was wealthy or poor, famous or unknown, powerful or impotent made no difference. αὐτάρκεια, then, is a sort of contentment, a mental independence and self-sufficiency from all things. This allows one to have προαίρεσις, which is the rational and free ability to make a judgment, that is to give or withold assent to an impression. When one practices correct judgment than a sort of ἀταραξία is achieved, this state of equanimity or imperturbability where one is untroubled by anything that is outside of one’s own control. The ultimate goal, therefore, being a state of ἀπάθεια where one is totally free from passion and living completely in accordance with nature.

Freedom, Philosophy, Momento Mori, & Amor Fati

There is a lot I admire about Stoicism. and I think that everyone could benefit from it. For it seems that it is no less applicable in ancient Greece or Rome than it is today in our modern society. We should find happiness within ourselves, and not be a sycophant for the approval of others. “When someone is properly grounded in life,” says Epictetus, “they shouldn’t have to look outside themselves for approval” (Discourses, 1.21.1). As I have grown and matured in life, I have realized that this is true, and living for the approval of others is no way to live.

As I mentioned previously, fear is the primary base emotion that can drive many of my decisions; however, this is also not a healthy way to live, and I have been on a quest for freedom in the most metaphysical sense of the term for by in large the past decade. Stoicism seems like an appropriate antidote to living a life where one is captive to fear. This can be done through the stoic concept of proper judgment wherein one can live a life with more equanimity. “The fruit of these doctrines is the best and most beautiful, as it ought to be for individuals who are truly educated: freedom from trouble, freedom from fear – freedom in general…What else is freedom but the power to live our life the way we want? Do you want to live your life in fear, grief, and anxiety? (Discourses, 2.1.19-24). The stoic concept of proper judgment is also very helpful knowing that one is in complete control over one’s mind, thoughts, actions, and judgments. When this concept is truly absorbed and appropriated, one can much more easily take accountability for all one’s actions or lack thereof, and avoid falling into the victim mindset (of course my Nietzschean and Jungian interlocutors are screaming!). We have self-determination (Discourses, 2.8.21) and free-choice (ibid, 2.10.1) which is itself unconfined and independent, and uniquely able to evaluate itself over, above, and against the other ruling faculties (ibid, 1.1.4)

The Stoics, just like the Cynics, the Platonists, the Peripatetics, the Epicureans, etc., all saw themselves, to a certain extent, as inheritors of the philosophy of Socrates. More specifically, they all believed that their philosophy was the one that was accurately continuing the socratic project. It’s no marvel therefore that the study of philosophy plays a prominent role in stoic dogma. Although what this means is drastically different from earlier greek Stoicism like that of Chrysippus when compared with the late roman Stoicism of Seneca: both stress the importance and role of philosophy as the only means whereby one can achieve virtue. “So return to philosophy again and again, and take your comfort in her: she will make the other life seem bearable to you, and you bearable in it” (Meditations, 6.12). Seneca, quoting Epicurus, puts it more bluntly, “To win true freedom you must be a slave to philosophy” (Letters from a Stoic, VIII).

The consolation of philosophy notwithstanding, there is a pervasive loneliness throughout Marcus’ Meditations, a grasping for meaning or value to avoid some sort of ancient form of nihilism: a wrestling with reality as it truly is, an amor fati. In one of my favorite aphorisms in the Meditations, Marcus poetically and poignantly writes: “In man’s life his time is a mere instant, his existence a flux, his perception fogged, his whole bodily composition rotting, his mind a whirligig, his fortune unpredictable, his fame unclear. To put is shortly: all things of the body stream away like a river, all things of the mind are dreams and delusions; life is warfare, and a visit in a strange land; the only lasting fame is oblivion. What then can escort us on our way? One thing, and one thing only: philosophy” (2.17). Nietzsche encapsulates this spirit, “My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it—all idealism is mendaciousness in the face of what is necessary—but love it” (Ecce Homo, 2.10). In many ways this is how I have lived and also how I view my life. While I don’t share in the fatalism of the Stoics, and have since shed my shared accordance with Nietzsche’s determinism (Nietzsche had a complicated view of free-will, but lends himself more towards determinism although not in a mechanistic sense, c.f. the will to power), I truly am grateful for all the things that have happened to me in my life and all my decisions, both good and evil–and by Jove there have been some evil things. Nevertheless, they have made me who I am today and I am simply a better human because of it, despite a latent yet stubbornly persistent melancholy. I am able to embrace life in all of its variegated forms, and as Nietzsche extols us to do, not simply endure it, but love it, in gratitude with a thankful heart (c.f. Meditations, 9.28; Nietzsche The Gay Science, 4.341).

In Marcus’ Meditations especially, there is an emphasis on not fearing death, and a constant reminder that death is always near, is natural, and will come inevitably. “The clearest call to think nothing of death is the fact that even those who regard pleasure as a good and pain as an evil have nevertheless thought nothing of death” (12.34). This momento mori , and the not so tacit jab at the Epicureans, I really love, because it keeps your life in the proper perspective amidst a culture that pretends that we are all going to live forever. “[From] earth unto earth. And why am I actually troubled? Dispersal [death] will come on me, whatever I do…but I revere it, I stand firm, I take courage in that which directs all (Meditations, 6.10). One more for emphasis, “All that you see will soon perish; those who witness this perishing will soon perish themselves. Die in extreme old age or die before your time – it will all be the same” (9.32).

Nowhere captures this spirit more than in the wisdom literature of the Hebrew Scriptures, “[For] you [will] return to the ground–because out of it were you taken. For dust you are, and to dust you shall return” (Gen 3:19); and again in Job, “All flesh would perish together, and man would return to dust (Job 34:14); and once more, “What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun” (Ecc 1:9). Marcus again states, “Nature gives all and takes all back. To her the man educated into humility says: ‘Give what you will; take back what you will.’ And he says this in no spirit of defiance, but simply as her loyal subject” (Meditations, 10.14). And Job once more, “Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked I will depart. The Lord gave and the Lord has taken away; may the name of the Lord be praised” (Job 1:21).

“Stoicism attempts to attenuate the full spectrum of human emotions because it judges the majority of these emotions to simply be an error.”

The God of Nature & Nature, the God

While I can continue on about additional auxiliary concepts of Stoicism that I like, for example, a simple life, avoiding ostentation, not engaging in superfluity, building up good habits, practicing mindfulness of thoughts, not just thinking about virtue but being a virtuous man, and more, I’ll avoid the pen. Perchance, this will be for another essay in the future. Nevertheless, there is, in my opinion, something that Stoicism simply cannot solve, and that is the complexity and variation of human psychology, the depth and spectrum of human emotions, and the different valences of the embodied human experience. Firstly, the Stoics’ prescriptive ethic is prescribed for all men, regardless of their differences. Stoicism therefore doesn’t take into account the variety of human personalities and inherited psychological traits that color experience.

Secondly, while the Stoics attempted to reach a state of ἀπάθεια, where one was completely without suffering or undisturbed passion, the irony is that the Stoics were pantheists. Thus for them, God is equivalent with nature, and Nature to God. God was therefore constantly undergoing movement, in flux, and therefore subject to suffering and never-ending change. I am reminded of the early fourth century A.D. Latin theologian Lactantius who, arguing against the Stoics, wryly retorted: “The Stoics…divide nature into two parts…God and the world, the Maker and the work…[But] sometimes they so mix them together, that God Himself is the mind of the world, and that the world is the body of God…Why, should I say that we cannot even plough without lacerating the divine body?” (Institutiones Divinae, 7.3). Of course, the answer is that the Stoics didn’t conceive of change as a negative passion like the Platonists did (subject to decay, imperfect), but simply maintained while there was goodness, kindness, and benevolence in God, there was no anger (this stoic concept is what Lactantius argues against in his treatise De Ira Dei [On the Wrath of God]), and therefore God suffers no evil as a part of the infinite historical cycle. Marcus explains, “A bitter cucumber? Throw it away. Brambles in the path? Go round them. That is all you need, without going on to ask, ‘So why are these things in the world anyway?’ That question would be laughable to a student of nature, just as any carpenter or cobbler would laugh at you if you objected to the sight of shavings or off-cuts from their work on the shop floor. Yet they have somewhere to throw their rubbish, whereas the nature of the Whole [God] has nothing outside itself [pantheism]” (Meditations, 8.50).

In my opinion, Stoicism attempts to attenuate the full spectrum of human emotions because it judges the majority of these emotions to simply be an error in assent and an improper judgment. Ergo, a passion that leads to pain, anxiety, or suffering. In my estimation, while there is a little room for certain emotions that they called εὐπάθεια, such as joy, calm, watchfulness, these were reserved only for the stoic sage who had achieved virtue, and not for those who were “on the path towards virtue.” The other emotions were considered bad, and everything else considered indifferent. While it’s true that these bad emotions can certainly bring about intense pain, suffering, or anxiety, sometimes pain is life’s greatest teacher. As Nietzsche eloquently put it, “This art of transfiguration is philosophy…constantly we have to give birth to our thoughts out of our pain and, like mothers, endow them with all we have of blood, heart, fire, pleasure, passion, agony, conscience, fate, and catastrophe…[For] only great pain is the ultimate liberator of the spirit” (Nietzsche, The Gay Science, Preface, III).

The Humanly Suffering God

Thus, the Stoics considered passions which cause pain and suffering not in accordance to Nature. Since in stoic theology Nature was God, not living according to Nature was also not living in accordance with the divine will, rational mind, and common good.1 There seems something inhuman about avoiding grief, sorrow, anguish, agony, fear, anxiety, and pain: all the suffering that life can hurl at us. When we look to Christ as the moral exemplar, far from seeing a stoic sage, we see a human, rather, a theanthropic being, who felt grief (Mk 3:5), distress (Matt 26:37), pain (Mk 15:15), indignation (Mk 1:41), and also cried (Jn 11:35). Leading up to his passion on the cross he says to his disciples, “My soul is exceedingly sorrowful, even unto death” (Matt 26:38). The God that is worshipped by the Christians is a God who paradoxically suffered and died. Taking Christ as the moral exemplar for the range of human emotions perhaps could be seen as sufficient, and yet there is a deeper theological axiom at work; viz., suffering as a part of the divine essence.

If the world is the canvas of God, suffering and evil therefore become necessary for the magnificent display of art, music, poetry, ingenuity, technological and scientific advancements, creativity, individuality, and diverse expressions of religion, myth, literature, and more. This divine becoming, which is our history, forges the human spirit in the hearth of the World Soul. While the Stoics urged all to live according to the divine nature, which would lead to a sort of apatheia, for it is Christianity, in contradistinction, that exhorts all to express the whole host of human emotions quite simply because this is also in accordance with the divine nature. The Cross, therefore, is not just expiation, but this theologia crucis becomes the historical manifestation of natura dei which is constitutive of the Trinitarian Godhead himself. Nietzsche’s madman declared the death of God, proclaiming that each of us are his killers (The Gay Science, 3.125). Furthermore, Hegel states: “The pure concept, however, or infinity, as the abyss of nothingness in which all being sinks, must characterize the infinite pain, which previously was only in culture historically and as the feeling on which rests modern religion, the feeling that God Himself is dead” (Hegel, Faith & Knowledge, 266).

For Hegel, and for Nietzsche, the death of God meant, the death of value, the death of the feeling of the knowledge of God. As Hamilton and Altizer so pointedly put it in their death of God theology: “God is dead. We are not talking about the absence of the experience of God, but about the experience of the absence of God” (Thomas JJ Altizer and William Hamilton, Radical Theology & the Death of God, 28). Yet the death of God must not always lead towards nihilism, because this means that there is a humanly suffering God. Nietzsche was incorrect when he excoriated all of us for killing God; for it was not us who killed God, it was God who killed God: it was his nature to do so. For it is the nature of God to incarnate himself and to suffer and die insofar as the Father participates, albeit in a unique way, with the god-forsakenness of Jesus on the cross. The German theologian Jürgen Moltmann explains, “This death itself expresses God. The death of Jesus is a statement of God about himself…[for] the self-surrender, the grief, and the death of the crucified Christ [lead us] back to the inner mystery in God himself” (The Crucified God, 288-289).

So what of the pain, suffering, and evil? Is there any teleology in world history? Friedrich Schelling soberly remarks that there is no easy answer to these questions, but “because God is a life, not merely a being…all life has a fate and is subject to suffering and becoming. To this, too, God has subjugated himself freely, ever since he separated the world of light from the world of darkness in order to become personal…Without the concept of a humanly suffering God, which is common to all the mysteries and spiritual religions of ancient times, all of history remains incomprehensible” (Schelling, Philosophical Investigations into the Essence of Human Freedom, 66). Yet the smattering of hope that one can cling to lies in the proleptic judgment of God, wherein the eschatological anticipation is accomplished in the resurrection of the crucified God. Moltmann concludes, “Jesus rose into the final judgment of God to which both kerygma and faith bear witness” (The Crucified God, 239).

Final Remarks

While I’ve mourned the loss of my old blue Kia (named Regine, after Kierkegaard’s ex-fiancee), I’m still waiting for this lady’s insurance company to admit fault and offer a settlement. I did, however, get a new car, thankfully. And while I’m not so sure the end of all things, I do know the resilience of the human spirit, however keenly aware I am of the current trajectory on the world-historical stage. Meanwhile, I can conclude in good faith with Marcus, who potently said, “The universe is change; life is judgment” (Meditations, 4.3.4). I only hope that this does not include any more car accidents.

-b

1. “The old Stoic tradition: (a) the cosmos is permeated by the divine Logos and its rationality corresponds to that of the divine being itself; (b) the seed of wisdom is innate in all men. Man comes to know the rationality of the cosmos with the aid of his innate ideas, his reason (like is known only by like), and in this way he achieves a life in accordance with his nature. But if nature (φύσις / physis) corresponds to God and is itself divine, then by a life in accord with nature and reason, man achieves a life in accord with God.” Jürgen Moltmann, The Crucified God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2015), 301-302.

Discover more from Blessed are the Poor in Spirit

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.